Chinese Art

Painting

Calligraphy

Printed Books

Porcelain

Stones and Jade

Chinese Art

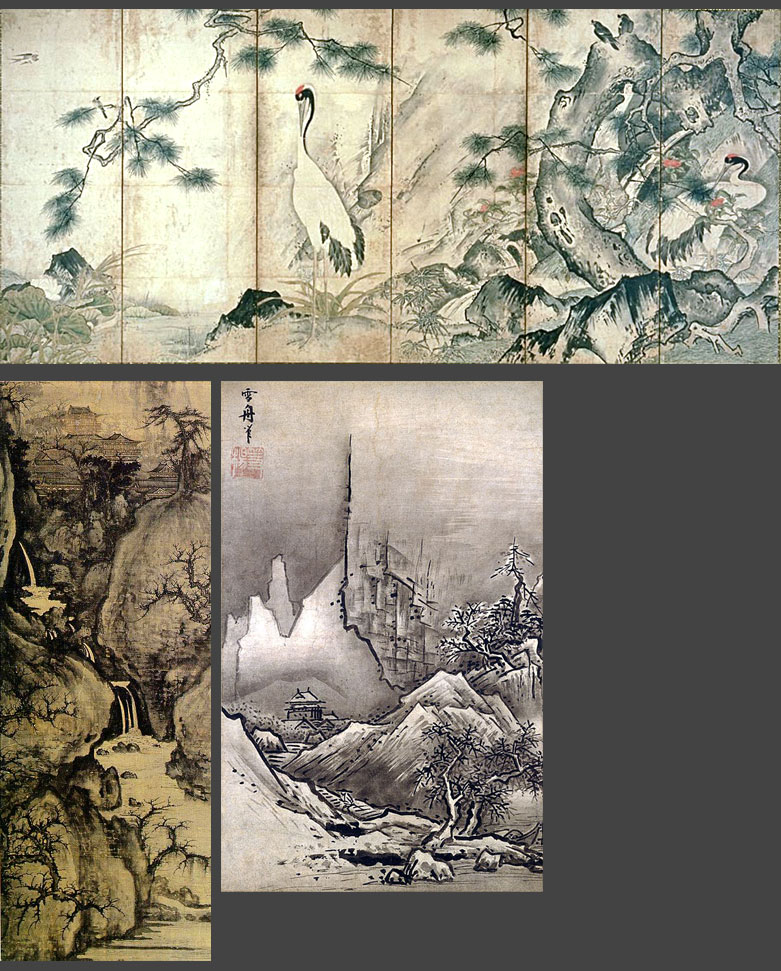

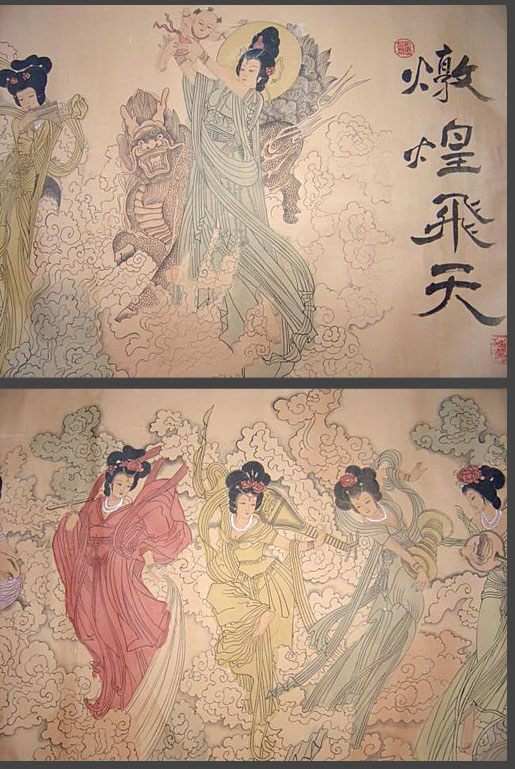

Painting

In the 4th century AD, painting began its rise as an art form. Not surprisingly,

the Chinese judged the worth of a painting by the quality of its brushstrokes.

The customary use of monochrome ink and silk canvases for paintings

made it impossible to erase or correct something once it was drawn,

so painters had to be masters at brushwork. Early paintings depicted

courtly scenes and natural vistas. Then, during the Song Dynasty (960

to 1279 AD the handscroll landscape paintings for which China is known

emerged as the dominant form of artistic expression.

Landscape painting, especially during the Song Dynasty and its successors,

the Yuan and Ming dynasties, did not depict a particular view of a particular

mountain or stream. Instead, painters would study nature and then try

to paint its essence. Birds and flowers were also painted in this way.

When humans appeared in the painting, it was often to show how grand

nature is and how insignificant we are.

The Chinese generally painted landscapes on 12-inch-wide silk fabrics

called handscrolls. About 20 feet long, the scrolls were meant to be

looked at by a few people at a time. Viewers unrolled the painting gradually,

seeing only a foot or so, moving right to left from scene to scene.

Usually, the scroll landscape revealed a small narrative or moral message.

Landscapes often featured calligraphy. The painter would, for example,

add a poem in the corner. Calligraphy, painting, and poetry were fast

becoming the most important arts in China, so it was fitting to combine

the three. Sometimes, however, calligraphy was added much later, after

the painter had died. Usually, the calligraphs would praise the work

or record the painting's provenance.

Chinese paintings on silk screens and paper.

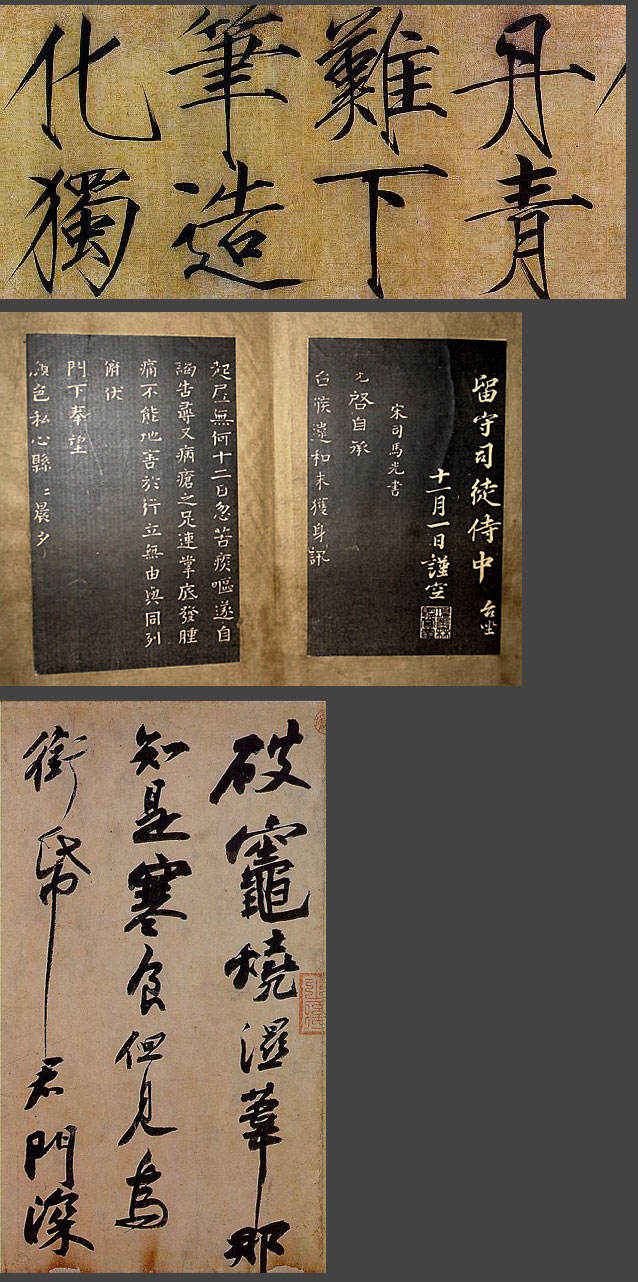

Calligraphy

Calligraphy, arguably China's most important form of art, also emerged

during the Bronze Age. Animal bones inscribed with "word pictures,"

called oracle bones, were used to tell the future. Someone would draw

a question on a bone, and a shaman would heat the bone until it cracked,

then "read" the answer according to the shape of the crack.Drawing

the calligraphs, even today, is considered an art.

The brushstrokes used for calligraphy are the same as in Chinese painting,

and a calligrapher's worth has always been based on the expressiveness

of his brushwork. Conventional wisdom says that calligraphy should reveal

the character of the writer while maintaining important structural elements.

It's difficult to overstate the importance of calligraphy in the history

of Chinese art. Indeed, calligraphy has served to unite the Chinese

over the millennia, evolving out of pictographs and ideographs, written

Chinese characters that may no longer resemble what they mean, but are

still exactly the same all over China. Separate regions speak in dialects

so different that they sound like unrelated languages. But everybody

in China uses the same characters—no matter what the pronunciation.

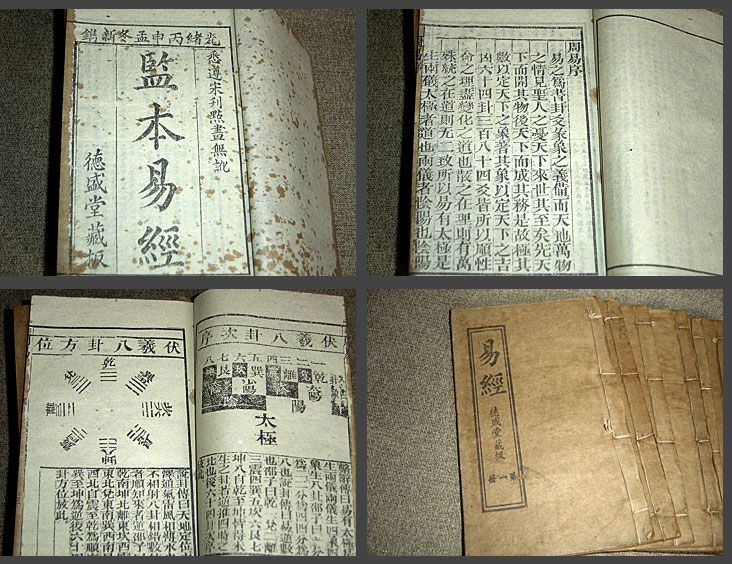

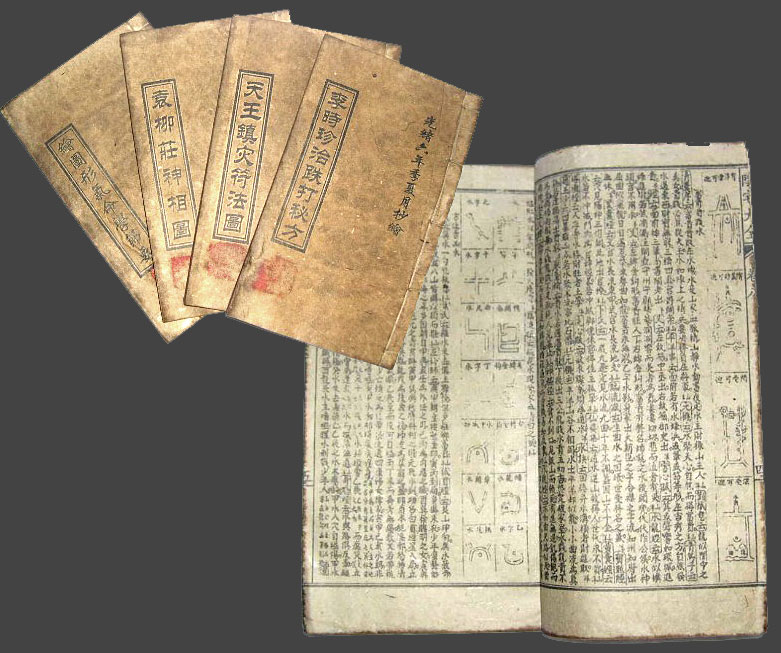

Though not calligraphy, but a printed

book, I still want to show you the following, an

early 20th century I Ching:

And further samples of early 20th century printed books. These books

and their page designs should give plenty of references for contemporary

design:

Porcelain

During the Song and Yuan dynasties, but especially during the Ming Dynasty,

the Chinese produced exquisite porcelain objects. First made around

the 5th or 6th centuries AD (about the same time the Chinese invented

paper), Chinese porcelain predated European porcelain by 1,000 years.

Interestingly, the most prized blue-and-white porcelains were made during

only a particular 10-year stretch, 1425 to 1435, during the Ming dynasty.

These porcelains are coveted for their perfect glazing, shape, and lively

dragon decorations.

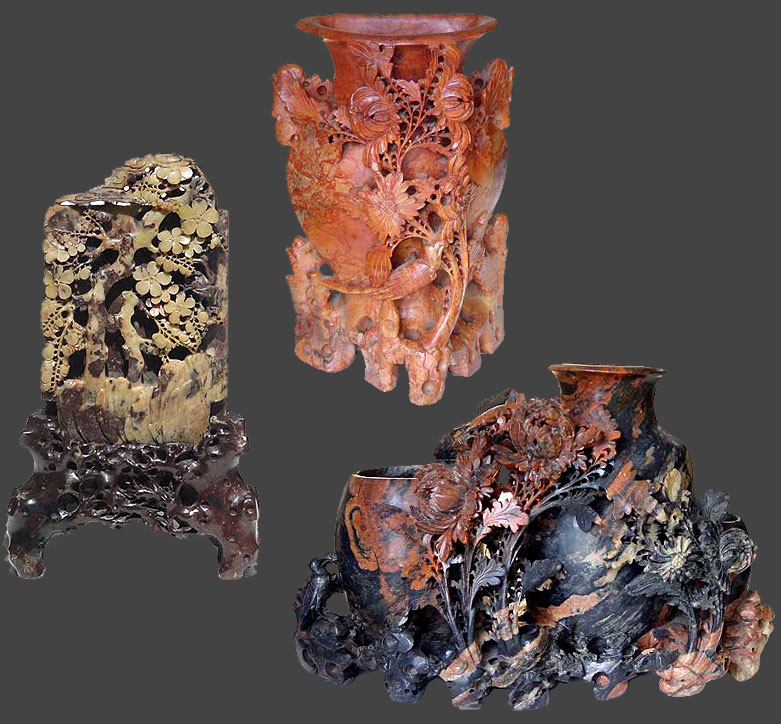

Stones and Jade

Soapstone Vases

Jade

Carved wood