Japanese

Art

Sumi-e

Printmaking

Ukiyo-e

Netsuke

Porcelain

Wabi Sabi

Zen Gardens

Architecture

Sumi-e

Sumi-e means: Black Ink Painting. Black ink on white paper, simple,

elegant and serene. Simplicity is the most outstanding characteristic

of Sumi-e. An economy of brush strokes are used to communicate the essence

of the subject.

"If we study

Japanese Art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophic and

intelligent, who spends his time doing what? In studying the distance

between the earth and moon? No. In studying Bismark's policy? No. He

studies a single blade of grass."

Vincent Van Gogh

The Philosophy of Sumi-e is contrast and harmony, expressing simple beauty and elegance. The Tai Chi diagram demonstrates the perfectly balanced interchange of the two dynamically opposed forces of the Universe, the dot represents integration.

Sumi-e employs these principles of nature's vitality in its design and execution. The balance and integration of these forces and the eternal interaction of Yin Yang are the ultimate goal of Sumi-e. The art of brush painting, aims to depict the spirit, rather than the semblance of the object. In creating a picture the artist must grasp the spirit of the subject. Sumi-e attempts to capture the Chi or "life spirit" of the subject, painting in the language of the spirit.

Patience is essential

in brush painting. Balance, rhythm and harmony are the qualities the

artist strives for by developing patience, self-discipline and concentration.

The goal of the brush painter is to use the brush with both vitality

and restraint. Constantly striving to be a better person because his

character and personality come through in his work.

Printmaking

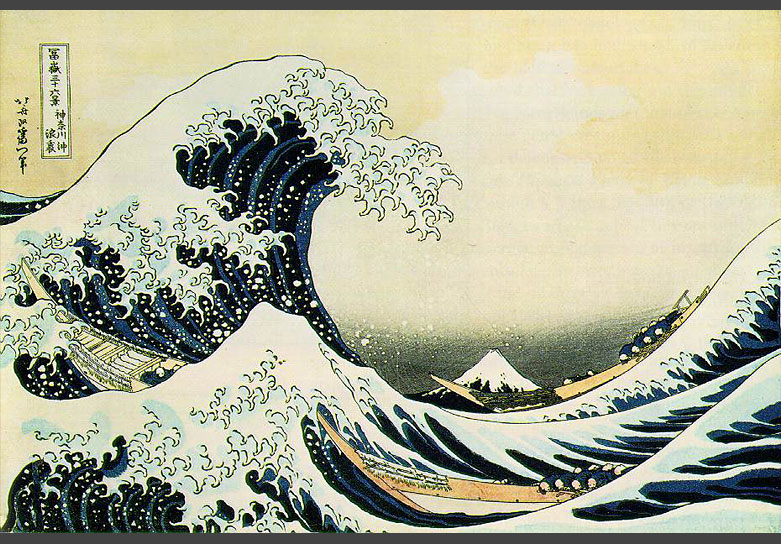

We start out with the Edo period printmaker Hokusai's

famous "Great Wave"...

The most influential Japanese master of landscapes and figure studies, Hokusai created many masterpieces throughout his long and productive life. Studying under Shunsho, Hokusai's earliest art was devoted to competent actor prints and figure studies in the style of his master. Then, in the first decade of the nineteenth century, Hokusai's tireless studies led him to examine both Western art and Chinese paintings and prints. He thus broke from the standard 'Ukiyo-e' style to forge a path for his own unique genius. This would lead him to some of the greatest artistic examinations of the relationship between man and nature in the history of art, such as, Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji (1831) and One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji (1834-1835).

Throughout his career Hokusai devoted much of talents to the art of the book. He became in fact close friends with some of Japan's most widely read novelists, poets and translators, such as Takizawa Bakin, Emba and Takai Ranzan. Hokusai's illustrative art is vital to an understanding of his superb genius. One authority writes, "The great strength of Hokusai's illustrations to these popular novels is the artist's enormous imagination and vision. His designs are really of great compositional vitality, almost unparalleled at the time. His heroes not only were an example to later followers; the strong emphasis on interaction between the figures, combined with visionary and balanced compositions must have been appreciated." * These words clearly apply to this brilliant, original woodcut.

(Matti Forrer, Hokusai,

Rizzoli, New York, 1988, p. 141 and pp. 258 & 259)

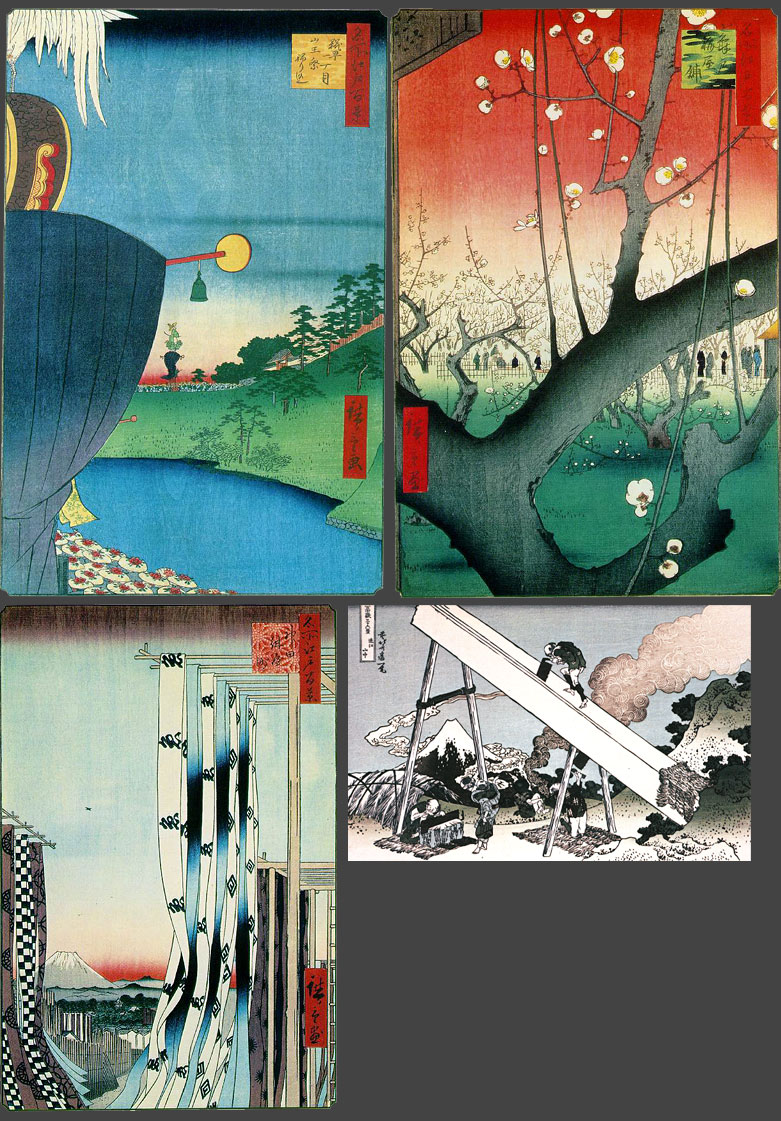

We

continue with the other Edo Woodblock printing master Hiroshige:

Undoubtedly, the two greatest masters of Japanese landscape art are

Hiroshige and Hokusai. Hiroshige, perhaps the most lyrical landscape

artist of any time, was born into a low ranking samurai family in the

capital city of Edo. He became a pupil of Toyohiro at the age of fifteen

and also studied the art of the Utagawa School. He started his career

as a book illustrator and then turned to portrayals of beautiful women.

It wasn't until seeing Hokusai's Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji that

Hiroshige turned almost exclusively to his famous landscape art.

As Hokusai's art is forever linked with the landscape of Mt. Fuji, Hiroshige's

art will always be best remembered for his scenes along the Tokaido

Road. This was the 490 kilometer route that joined the two great capitals

of Kyoto and Edo (Tokyo), and formed a sacred pilgrimage of fifty-three

stages or places for all who traveled it.

Hiroshige's first series of views of the fifty-three Stations of the

Tokaido was published in 1834. During the following years this great

artist produced many amazing woodcuts of views in and around Edo, Osaka,

Ohmi and Kyoto. Yet, almost until his death, he kept returning to the

spiritual landscape scenes of the Tokaido Road.

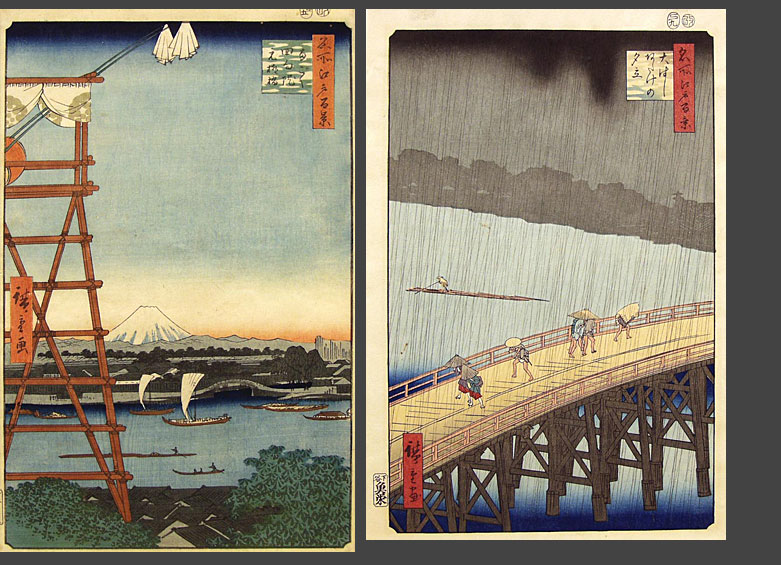

2 more prints by Hiroshige

<<<top

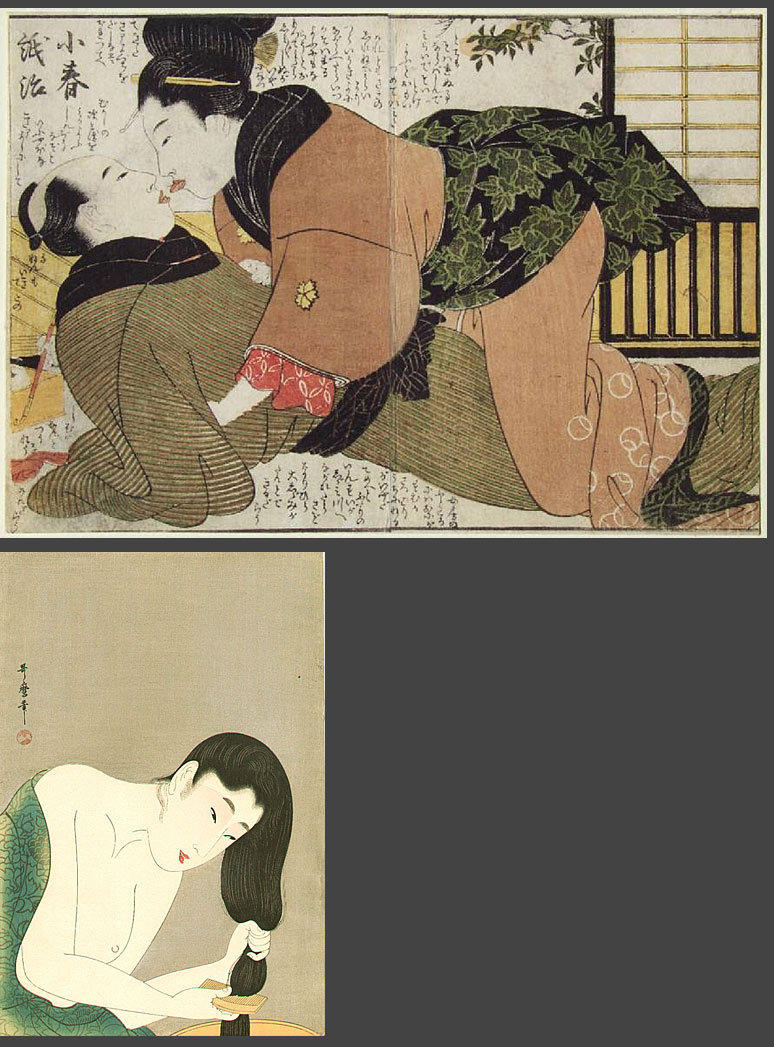

Ukiyo-e

"Images of the fleeting world..."

The art of ukiyo-e originated in the metropolitan culture of Edo (Tokyo)

during the period of Japanese history, when the political and military

power was in the hands of the shoguns, and the country was virtually

isolated from the rest of the world. The average citizen's mood of Edo

period (1603 - 1867) was an extremely buoyant and joyful one, not the

transitory, heavy atmosphere characteristic of the troubled middle age

and these woodprints reflect that. It is an art closely connected with

the pleasures of theatres, restaurants, teahouses, geisha and courtesans

in the even then very large city.

Many ukiyo-e prints by artists like Utamaro and Sharaku were in fact posters, advertising theatre performances and brothels, or idol portraits of popular actors and beautiful teahouse girls. But this more or less sophisticated world of urban pleasures was also animated by the traditional Japanese love of nature, and ukiyo-e artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige have had an enormous impact on landscape painting all over the world.

The imagery in

some Ukiyo-e prints is highly erotic. I have not included any of these

since unfortunately I couldn't find any that pleased me enough visually.

However let me not stop you from taking a peek...

http://www.ukiyoe-gallery.com/gallery9.htm

Anonymous Artist

Two prints by Utamaro

Netsuke

Netsuke served both functional and aesthetic purposes. The tradtional

Japanese dress, the kimono had no pockets. The robes were hung together

by a broad sash (obi), so items that were needed to be carried were

held on a cord tucked under the sash. The hanging objects (sagemono)

were secured with carved toggles (netsuke). A sliding bead (ojime) was

strung on the cord between the netsuke and the sagemono to tighten or

loosen the opening of the sagemono.The best known accessory was the

inro, a small box used by the wealthy for carrying medicines and seals.

Netsuke were also used to secure purses, and were widely used to hold

the tobacco pouches that became almost universal with the introduction

of smoking in Japan.

The quality of Netsuke was variable. As everyday objects many were carved quickly with left over materials. Netsuke could be made using a variety of materials mainly wood, and ivory (also shell, bone, horn, even metal and precious stones). Wealthier people would have finer netsuke, and it could be possible to tell the status of an individual by the quality of their netsuke.

There are several types of netsuke including: manju, round or square button like boxes; and kagamibuta, comprising a metal lid and a bowl; and katabori. The range of subjects included all manner of animals, birds, the heores and villains from folklore, the immortals and mythical animals of Japanese legend, the grotesque and the amusing.

Porcelain

The manufacture

of porcelain came late to Japan. Legend has it that the Korean potter

Ri Sampei (1579-1655), who had been brought to Japan at the age of 19,

found clay for porcelain production at Izumiyama near Arita, established

a kiln at Tengudani and fired the first plain white, and the first underglaze

cobalt blue porcelains in Japan.

From 1620-28 experimentations took place in the Arita area to meet orders placed by Chinese and South East Asian merchants at the port of Hirado. In 1641 the trading location was changed by the Japanese gouvernment to the island of Deshima in the Nagasaki harbor.

Arita is still the best known area for porcelain production and most Japanese porcelain does come from this area. By the mid 19th century kilns all over Japan produced porcelain, some characteristically distinctive from others.

Wabi

Sabi

Wabi-sabi is the

quintessential Japanese aesthetic. It is a beauty of things imperfect,

impermanent, and incomplete. It is a beauty of things modest and humble.

It is a beauty of things unconventional...

It is also two separate words, with related but different meanings. "Wabi" is the kind of perfect beauty that is seemingly-paradoxically caused by just the right kind of imperfection, such as an asymmetry in a ceramic bowl which reflects the handmade craftsmanship, as opposed to another bowl which is perfect, but soul-less and machine-made.

"Sabi" is the kind of beauty that can come only with age, such as the patina on a very old bronze statue.

Wabi and Sabi are independent word stems in normal speech. They are brought together only to make a point about aesthetics. Sabi is most often applied to physical artistic objects, not writing. A well-known examplar of what one would call a "wabishii" object: black spit polish boots with dust on them from the parade ground. Many Japanese pots, the expensive ones, are dark and mottled -- wabi. "Sabishii" is the normal word for "sad", as is, that was a sad movie.

Architecture

Chinese architecture

has historically influenced that of Japan. In spite of this, there are

still major differences between the two. One variation with Japanese

architecture typically placed people on the floor to sit, whereas that

of China had them sitting in chairs. This custom began to change though

in the Meiji period (1868-1912).

Another influence, besides lifestyle, is the climate and the fact that Japan suffers from major earthquakes. Japanese have to plan according to the climate, the seasonal changes and the earthquakes. Since most of Japan has long, hot summers, the houses reflect that by being somewhat raised so that air can move all around. Wood is a popular choice for material because it adjusts well to earthquakes and works well with season changes (cool in summer, warm in winter).

Buddhism as well

has greatly influenced Japanese architecture since it's introduction

from China during the Asuka period (593-710). Horyuki Temple was built

in 607 under the influence of Buddhism, and was registered in 1993 as

a UNESCO World Heritage property. The layout of this temple has been

unchanged and preserved over the years. The Buddhist deity worshipped

at the temple is housed in the main hall, which is the oldest wooden

structure in the world and the center of the entire complex.

Zen

Gardens

Karesansui, or the

"dry-landscape" style japanese gardens have been in existence

for centuries, but it wasn't until the late sixth century with the advent

of Zen Buddhism did "dry style" gardens began to evolve. The

earlier gardens were created where one could enter and walk around and

much larger in scale. Around the eleventh century, zen priests adopted

the "dry landscape" style and began building gardens to serve

a different purpose. They were to be used as an aid to create a deeper

understanding of the zen concepts. Not only was the viewing intended

to aid in meditation but the entire creation of the garden was also

intended to trigger contemplation. By the late 1200's, the basic principles

had been established and up to the present day, they have been refined

and extended. The garden created by the zen priest are called "kansho-niwa"

or contemplation garden and termed by many today as " zen gardens

".