Input

Since Turkish

Art and Design is part of the larger tradition of Islamic

Art, some

introduction

into the basic premises of Islamic Art will be in order:

Ornamentation and abstraction

With the spread of Islam outward from the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh

century, the figurative artistic traditions of the newly conquered lands

profoundly influenced the development of Islamic art. Ornamentation in

Islamic art came to include figural representations in its decorative

vocabulary, drawn from a variety of sources. Although the often cited

opposition in Islam to the depiction of human and animal forms holds true

for religious art and architecture, in the secular sphere, such representations

have flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures.

The Islamic resistance to the representation of living beings ultimately stems from the belief that the creation of living forms is unique to God, and it is for this reason that the role of images and image makers has been controversial. The strongest statements on the subject of figural depiction are made in the Hadith (Traditions of the Prophet), where painters are challenged to "breathe life" into their creations and threatened with punishment on the Day of Judgment. The Quran is less specific but condemns idolatry and uses the Arabic term musawwir ("maker of forms," or artist) as an epithet for God. Partially as a result of this religious sentiment, figures in painting were often stylized and, in some cases, the destruction of figurative artworks occurred. Iconoclasm was previously known in the Byzantine period and aniconicism was a feature of the Judaic world, thus placing the Islamic objection to figurative representations within a larger context. As ornament, however, figures were largely devoid of any larger significance and perhaps therefore posed less challenge.

As with other forms

of Islamic ornamentation, artists freely adapted and stylized basic human

and animal forms, giving rise to a great variety of figural-based designs.

Figural motifs are found on the surface decoration of objects or architecture,

as part of the woven or applied patterns of textiles, and, most rarely,

in sculptural form. In some cases, decorative images are closely related

to the narrative painting tradition, where text illustrations provided

sources for ornamental themes and motifs. As for manuscript illustration,

miniature paintings were integral parts of these works of art as visual

aids to the text, therefore no restrictions were imposed. A further category

of fantastic figures, from which ornamental patterns were generated, also

existed. Some fantastic motifs, such as harpies (female-headed birds)

and griffins (winged felines), were drawn from pre-Islamic mythological

sources, whereas others were created through the visual manipulation of

figural forms by artists.

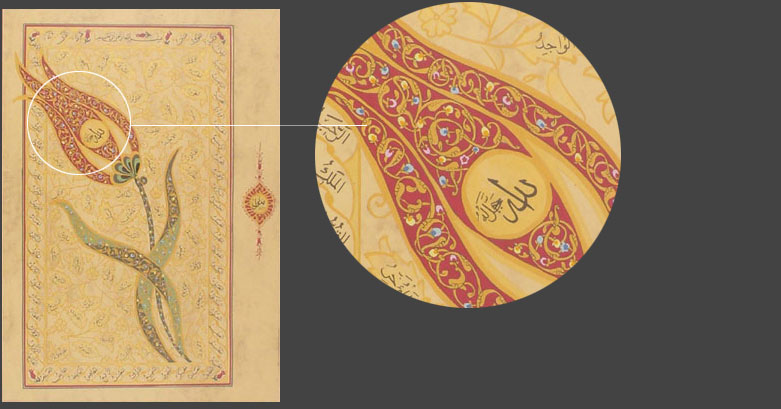

Calligraphy

is the most highly regarded and most fundamental element of Islamic art.

It is significant that the Quran, the book of God's revelations to the

Prophet Muhammad, was transmitted in Arabic, and that inherent within

the Arabic script is the potential for developing a variety of ornamental

forms. The employment of calligraphy as ornament had a definite aesthetic

appeal but often also included an underlying talismanic component. While

most works of art had legible inscriptions, not all Muslims would have

been able to read them. One should always keep in mind, however, that

calligraphy is principally a means to transmit a text, albeit in a decorative

form.

Objects from different periods and regions vary in the use of calligraphy in their overall design, demonstrating the creative possibilities of calligraphy as ornament. In some cases, calligraphy is the dominant element in the decoration. In these examples, the artist exploits the inherent possibilities of the Arabic script to create writing as ornament. An entire word can give the impression of random brushstrokes, or a single letter can develop into a decorative knot. In other cases, highly esteemed calligraphic works on paper are themselves ornamented and enhanced by their decorative frames or backgrounds. Calligraphy can also become part of an overall ornamental program, clearly separated from the rest of the decoration. In some examples, calligraphy can be combined with vegetal scrolls on the same surface though often on different levels, creating an interplay of decorative elements.

Text

compiled from

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/figs/hd_figs.htm

Designs and

Patterns...

Colours..

Calligraphy...

Miniatures...

Wood...

Metal...

Textile...

Ceramic...

Architecture

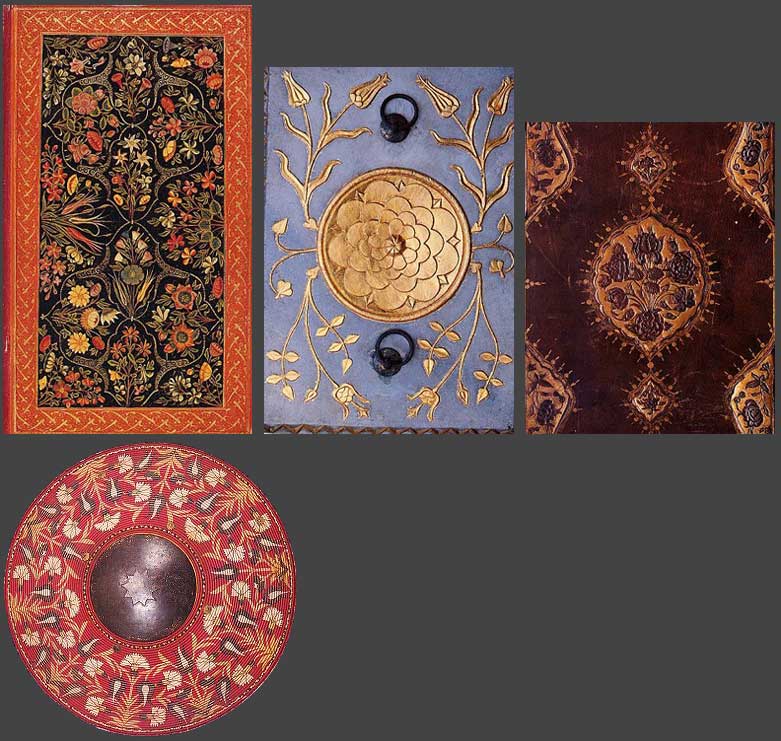

Designs and Patterns

Turkish Design

centers on floral and ornamental patterns and shapes as can be found ceramicware,

metalwork

and woodcarving

and in geometric shapes and patterns as can be

found in rugs and kilims as well as masonry work. What needs to be particularly

observed is that these patterns, shapes and motifs are usually designed

symmetrically.

Floral Designs and Motifs can be divided

inyo yhe following 3 categories:

01// Rumi The motifs which have been most

often employed in illumination are rumi, consisting of stylized wings,

beaks and legs of birds and animals;

02// Munhani, serried curves popular with

the Selçuks;

03// Hatayi, which are stylized floral motifs;

and clouds, a swirled effect of Chinese origin.

Rumi Ornaments

Hatayi Ornaments

Various Rumi and Hatayi Designs on leather, fabric and weaving.

Geometric Shapes and Patterns

Can be found in kilims as well as woodwork and masonry.

<<<top

There are the two main colour schemes that, in combination with white, black and tones of gray work very well for Turkish style design.

01// Turquoise and Blues: As inspired by ceramic tiles.

<<<top

Calligraphy

The traditional turkish calligraphic style is called Divani and has soft, flowing, curvilenear characteristics. Particalarly interesting are the zoomorphic calligraphic works of the Bektaşis. Kufic calligraphy is more Arabic than Turkish but can be used where a more broadly middle eastern style is called for.

The Tuğra of Suleyman the Magnificent

(Divani Calligraphy)

<<<top

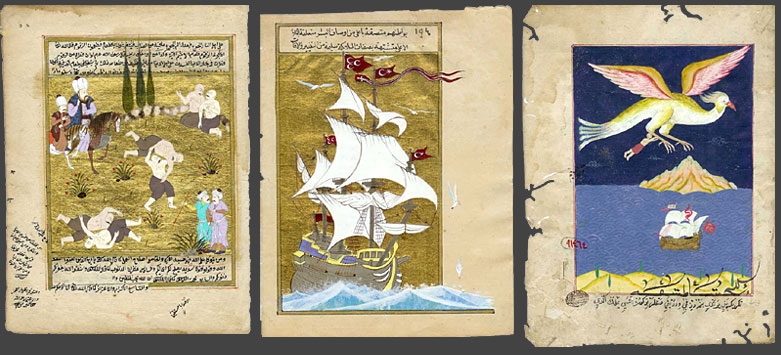

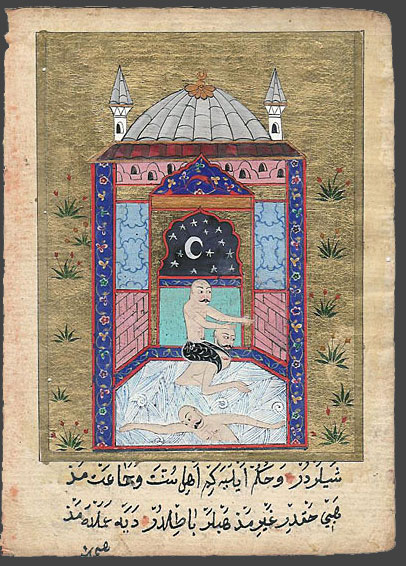

Turkish miniatures are less ornate and detailed than Persian ones, but their compositional and coloristic strength makes them as powerful and compelling. Their predominant colours are earthy and natural colours complemented with goldleaf. But initially we shall look at miniatures by Mehmet Siyahkalem, a Central Asian miniaturist of the 13th century, still very much under the influence of his Shamanic roots as well as Oriental Art:

Mehmet Siyahkalem school

Miniatures of the Ottoman Era

<<<top

Predominantly geometric shapes but also some very fine Rumi patterning as well as calligraphy

<<<top

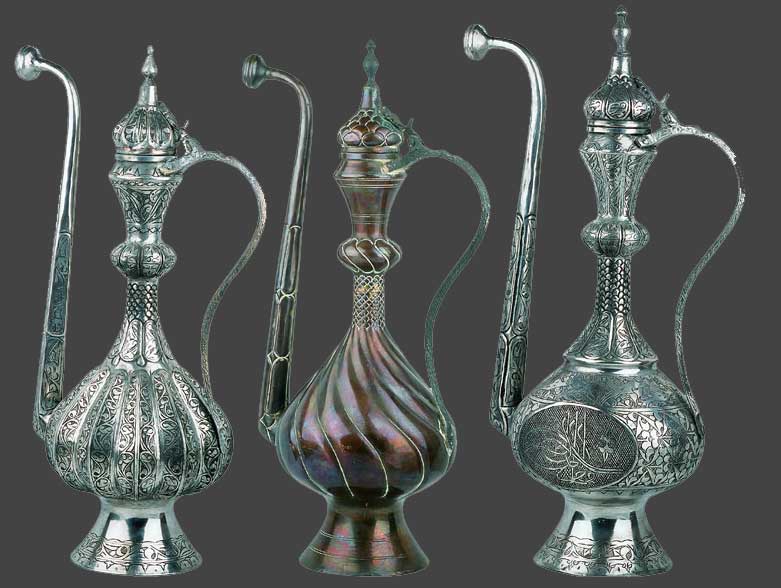

Calligraphy, Rumis and geometric designs as well as some very interesting and graceful 3D shapes.

Pitchers from Gaziantep

Copper Plates from Gaziantep

<<<top

Note the earth tones due to the natural dyes.

<<<top

Floral (hatayi) designs as well as rumis. Predominant colours blues and turquoise.

<<<top

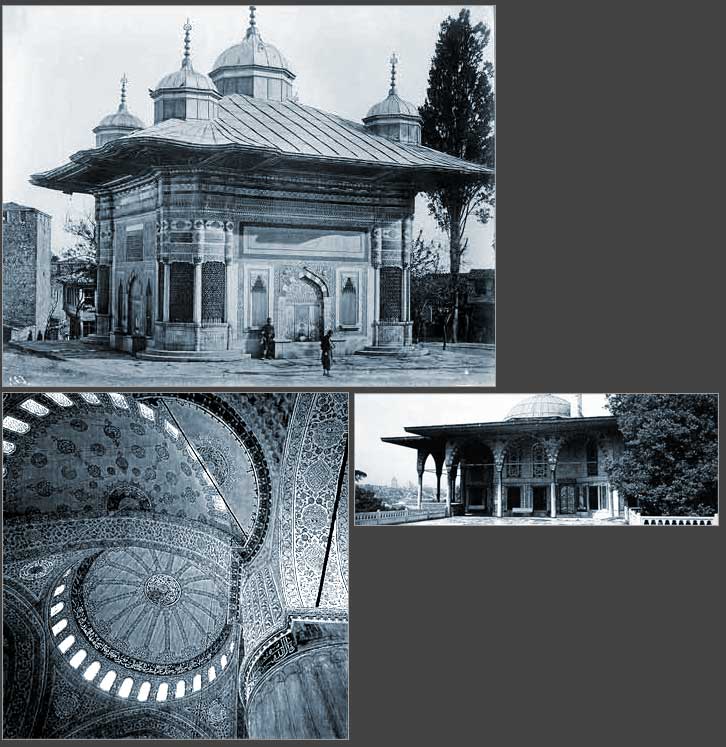

Ornate, symmetrical, opulent, spacious.

<<<top